We would like to begin this section with a quote from two visitors who have perfectly captured what drives the museum in creating projects for and with the community:

The museum preserves the memory of the community and serves as an educational reference for younger generations, helping to develop historical awareness and a sense of cultural identity

Stefo&Vivi. TripAdvisor Review

Every museum, and especially a territorial museum like the one in Bracciano, belongs to its community. It only truly fulfills its purpose when the community recognizes it as its own. Naturally, the community should play an active role in shaping and implementing the museum’s activities, contributing to the mission of preserving the heritage it safeguards so that it may be shared and passed on to future generations.

Every cemetery is a place that preserves the stories of cities. Bracciano Sottosopra: Memorie e Storie dal Cimitero (Bracciano Upside Down: Memories and Stories from the Cemetery) is a project that offers a sound itinerary within the cemetery. It collects personal narratives and reflections from citizens, making them accessible through audio recordings. The stories of Sonia Boffa, Giuseppe Curatolo, Massimo Giribono, Mario Gentilucci, Aldo Marziali, Massimo Mondini, Nerina Orsini, Marco Pastonesi, Cecilia Sodano, and Stefano Valente are featured on the Loquis audio platform, where they can be enjoyed by listeners. Bracciano sottosopra is the idea of Cecilia Sodano and was realised by Fernanda Pessolano of the Association TiconZero.

The ‘Preserving Memory’ project involves the establishment of an archive of testimonies with the collection of 20 short films through which the community tells its story.

2004. The project is ongoing, we are collecting testimonies from citizens. Among those interviewed are Salvatore Pierini, a key figure and organizer of the town’s festivals, particularly the Feast of the Holy Saviour; and Clara Canini and Sisto Mercantini, proprietors of a historic pork butchery.

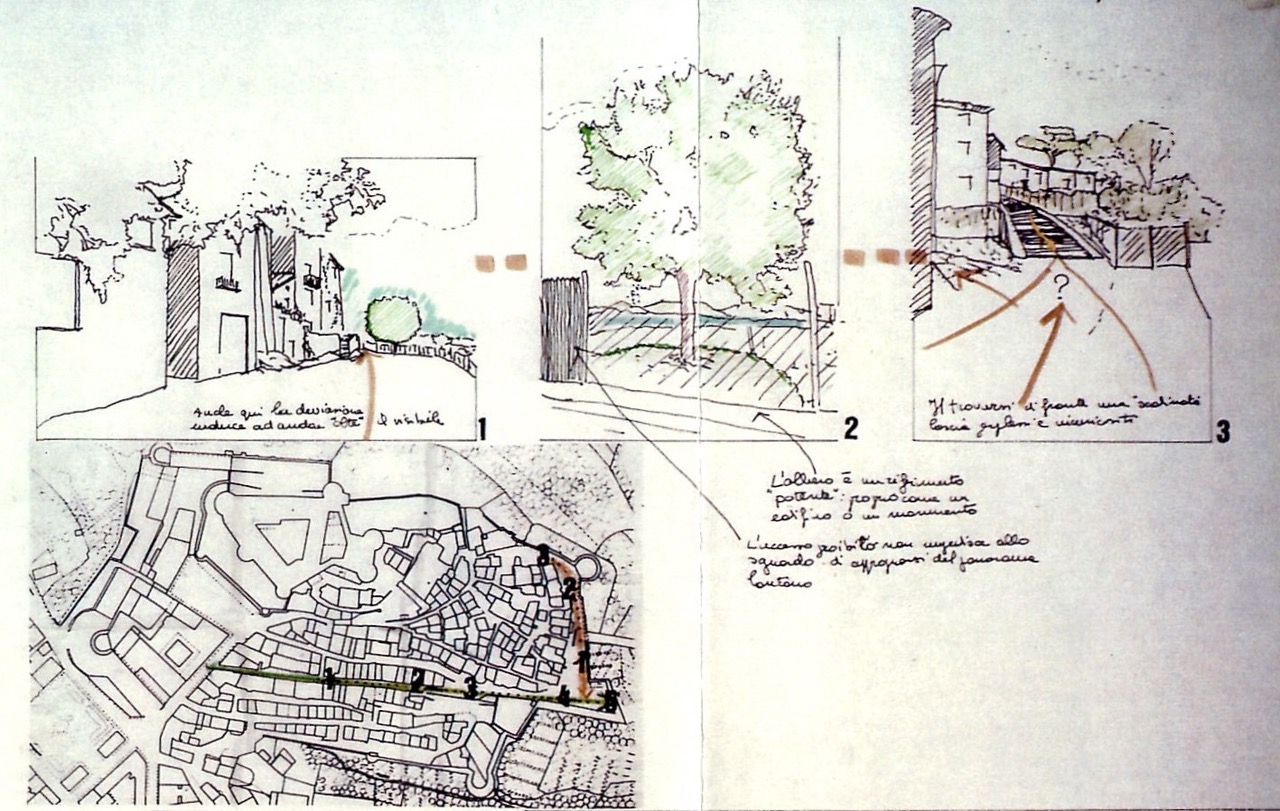

Community maps are creative representations of a territory, showcasing both its physical elements (such as landscapes, buildings, and the environment) and its intangible aspects (including craft knowledge, legends, historical events, and the emotions or memories tied to specific places). The process of creating a community map serves as a form of identity self-representation, capturing cultural heritage as it is experienced and perceived by the population involved. It is a collective narrative, weaving together stories, tales, and experiences that connect the past, present, and future. The Municipal Museum has embarked on the creation of a Community Map to highlight the cultural heritage valued by local inhabitants.

As of 2024, the project is ongoing. We are working closely with our expert, Architect Irma Visalli, to finalise the map and are currently seeking mediators to facilitate discussions at the meetings with the community.

An event realised in 2011 with the aim of raising awareness of the history of the Renaissance in Bracciano. During 15 days in December, conferences on history and art history, Renaissance music and dance performances, and workshops on Renaissance food were offered. The University of Tuscia, a partner in the event, organised the lectures; the local Slow Food association organised the workshops on Renaissance gastronomy; and local restaurateurs and pastry shops in the town centre offered their guests Renaissance menus based on recipes provided by the museum.

The centrepiece of the event was the theatre play ‘Io ti adoro bella’, produced by the museum, which tells the story of the Duke of Bracciano Paolo Giordano Orsini and his wife Isabella de’ Medici, who lived in the 16th century. The show helped to spread the historical truth about the two figures. The Municipality of Rome gave its patronage because the set design of the play is based on documents from the Orsini archive, preserved in the Archivio Storico Capitolino.

The evolution of the concept of cultural heritage

Edited by Director Cecilia Sodano

From the World Heritage Convention, the concepts of natural heritage and landscape in the international documents joins and then overlaps at that of heritage, which includes the landscape bearer of special value.

While considering that the debate on these issues is not the result of an organic evolution, it is nevertheless possible to outline a trend line within which the idea of heritage is developed over time.

Initially conceived as a set of material objects rigidly corresponding to the two categories of nature and culture, the concept of heritage is then expanded through an interdisciplinary approach that has included not only tangible and intangible elements, but also ideas and values.

The reflection on landscape and the cultural landscape has been an important hub of this process, inextricably linking nature and culture, people and places, tangible and intangible elements.

The concept of heritage was further expanded with the European Landscape Convention (2000) and the Faro Convention (2005), that consider the landscape and heritage as a fundamental resource for human well-being and for sustainable development. Both European documents have shifted the focus from the object landscape/heritage to people called to perceive/recognize it. This has opened new perspectives for public participation in a vision that moves from the object to the action, from product to process.

Involvement in the process of recognition of the value of the landscape / heritage by the community involves shared responsibility for the protection, conservation and, in the case of landscapes, management and planning.

This responsibility involves museums significantly, which is entrusted with the important role indicated by the above described outcome of the Resolution of the 24th General Conference of ICOM, which constitutes a major challenge for years to come.